The National Park Service has released its final general management plan that sets the parameters for development and preservation at the Lincoln Home National Historical Site for at least the next 15 to 20 years. It matters, even to the many Springfieldians who visit the place only to show visiting new in-laws around, since the agency is responsible for maintaining one of the nation’s most precious historic sites.

Among the larger goals of the new plan is to “offer visitors a strong sense of the neighborhood as Lincoln knew it” when he left for the capital. That, in broad strokes, has been the goal of the NPS since the feds acquired the four-block site along Eighth Street in 1971. How they intend to do it, however, has changed.

When the NPS took over, it cleared nearly a dozen lots along Eighth Street of any structures that had not been standing when the Lincolns lived there. Backers had vaguely promised to “recreate” the Lincoln-era Eighth Street, but restoring the house and building new visitor facilities came first. The denuded lots have, with one or two exceptions, stood empty ever since. Happily, the new plan is to put buildings back onto the empty lots nearest the Lincolns’ house in the form of period replicas – what the agency calls “full-scale structural exhibits” – of the Burch, Brown, Carrigan and Irwin houses.

While the historic landscape within this core of the site would be “recreated as completely as possible,” the eight vacant lots elsewhere on Eighth Street will remain unbuilt-on. Agency planners opted against erecting “ghost houses” of the sort used to suggest the presence of Benjamin Franklin’s long vanished house in Philadelphia, where a timber frame of the vanished structure outlines its missing walls and roof line, even the chimneys. (See “Ghost Houses,” Nov. 20, 1990.) Instead, the dimensions of the missing houses will be suggested by outlines of the original foundations.

Is it the lack of data that is keeping those lots vacant or the lack of money? For 40 years now, the local NPS staff has tried to develop the site according to its own rigorous standard, which boils down to: Do the job right, whatever the cost. Unfortunately, its parent is a Congress whose inclination these days seems to be to do very few jobs right, whatever the cost. The original vision of recreating the entire street is dismissed in the new plan on grounds of its “excessive costs.”

The NPS states that it could not reconstruct any of those houses because it lacks information about what they looked like. A mere simulacrum will not do, only an exact exterior replica, which is why the NPS rejected the Illinois Historic Preservation Agency’s urging to erect best-guess copies of these buildings. However, in constructing its own “full-scale exhibits,” the agency has acknowledged its willingness to “use conjecture where historical evidence is not available.”

We must wonder too whether even the planned reconstructions within the core will be built anytime soon. A few years ago the NPS was finally able to do the research needed to guide the eventual reconstruction of the Carrigan house (immediately north of the Lincoln house) and the Burch house (immediately west across the street). (See “The neighbors next door,” March 24, 2005.) The hope to have these open in time for the Lincoln bicentennial in 2009 was disappointed for lack of funding, although a barn-like structure at the rear of the Carrigan lot will be built to house public toilets. Indeed, in the 40 years since the NPS took over, money has been available to reconstruct only one house, the Arnold house immediately south of the Lincoln house.

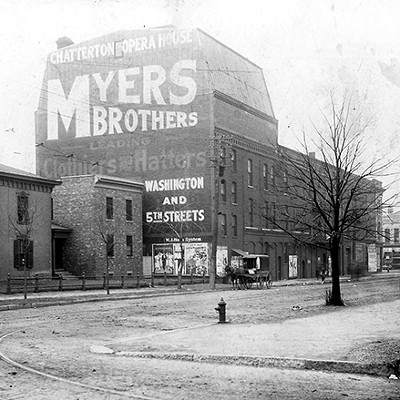

I’m not sure it will matter much. The agency has dubbed its preferred management approach “A Retreat From Modern Life in the Heart of the City,” but the finished historic core won’t retreat very far. Flush toilets and water will be available next door to the Lincolns’ house, which visitors approach on streets of gravel rather than the original dirt. There are no clothes hanging on wash lines, no peeling paint on the fences, no unmowed grass in the yards as there would have been in Lincoln’s day. Period photographs show weeds growing in the sidewalks in front of the house, and a sagging back fence; a detail from one photo is captioned by the NPS, “Mr. Lincoln was not known as ‘Mr. Fixit.’” You wouldn’t know it by touring the grounds today.

In short, the site will continue to be maintained according to a rigorous period standard, except when it isn’t. The new houses and other structures may meet museum-level curatorial standards as replicas, but they are likely to remain unconvincing as history because of the agency’s fussy suburban aesthetic. Oh well. Further preaching about the houses on Eighth Street would be as futile as admonishing Israel about houses on the West Bank. The feds are sovereigns on Eighth Street now.

Contact James Krohe Jr. at [email protected].