Long before the designated hitter, November World Series night games and $30 million salaries there was a game of baseball that many fans would probably recognize in its rudimentary form. Here in Springfield, we might not recognize the Capital, Lone Star, or Dexter Base Ball Clubs but they were all teams from our community that played in the post-Civil War era in central Illinois. Robert Sampson, a former central Illinois newsman and now editor of the Journal of the Illinois State Historical Society, has provided baseball fans and local history enthusiasts with a brief but extraordinary study of the game in its infant years. This was when local communities found their own fields of dreams, when civic pride led to paid professionals, and when rules disputes often resulted in baseball games ending in brawls.

Ballists, Dead Beats, and Muffins: Inside Early Baseball in Illinois is a delightful collection of history and baseball anecdotes for both casual and serious baseball fans. The muffins of the title were players of limited fielding ability. They could hit but were not very good in the field. Centuries later they would find their place in modern day baseball lineups as designated hitters. Published by University of Illinois Press, Inside Early Baseball was officially released May 2.

Baseball is more than a game for many fans. It is a lifetime experience. Robert Sampson's vivid account reminds us how the game began and why we anxiously wait every season for another Opening Day.

The book is not lengthy, the text is only 164 pages. But there is great detail in the journey across the Illinois communities that hosted teams and manipulated the still nascent rules of baseball in an effort to gain some advantage over the team from a neighboring community. In addition to the text, Sampson includes nearly 70 pages of appendices and notes. That material adds substantial information to the baseball saga. Readers learn, for example, that the various baseball teams across Illinois included attorneys, state employees, bankers, postal workers, insurance agents and engineers. In the 1970s and 1980s members of those same professions were still playing on softball teams in leagues organized at Riverside Park and the Brown Bomber Ballpark, a baseball facility located near Abraham Lincoln Capital Airport.

The saga of baseball in central Illinois also begins with a reminder that in both baseball and the world things may change, but they basically remain the same. On Oct. 18, 1869, Quincy, Illinois, welcomed to its fairgrounds the professional baseball team, the Cincinnati Red Stockings. The team had barnstormed across America, traveling as far west as San Francisco. Throughout their trip the Red Stockings had been undefeated and would now face the hometown Occidental Senior Base Ball Club.

The Red Stockings were the first professional baseball team in the land. Newspapers reported that only one player on the squad was from Cincinnati, the rest had been lured to the team by money. The Decatur Magnet, reporting on the game, observed that "Base ball (it was then two words) is being killed by the growing custom of employing professionals to do the hard work and play the matches." But then, just as now, fans flocked to see the game. The Red Stockings demanded a guarantee of $250 plus expenses for the game. They were paid, a large crowd attended and Cincinnati prevailed over the Quincy team by a score of 51 to 7. It turned out to be the final game for the Quincy team. Professional baseball had arrived in Illinois.

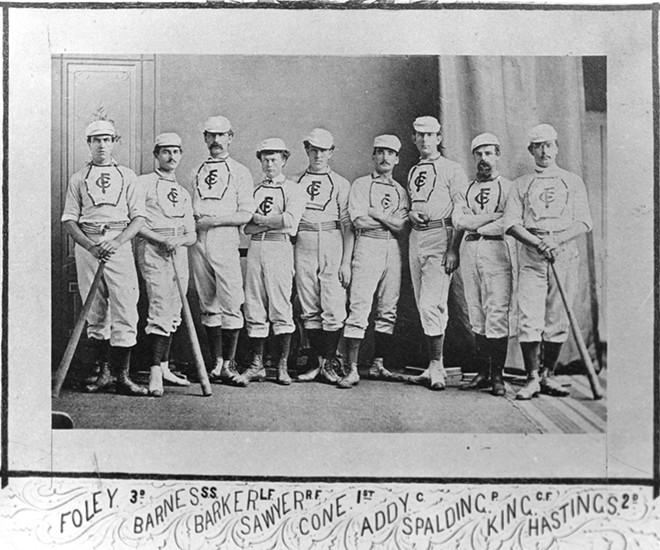

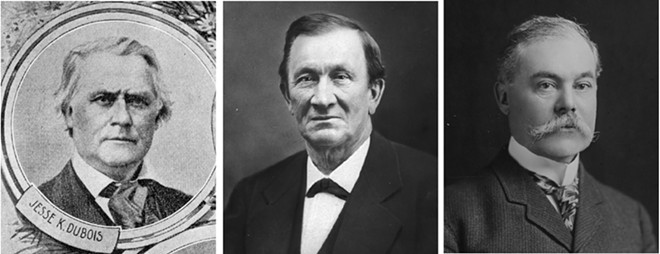

In Springfield the creation of a baseball team followed a tradition familiar to most denizens of the capital city. Two businessmen, Jesse Dubois, a Republican and Jesse Starne, a Democrat, both former state officeholders, organized the Capital Baseball Club in 1866. At their organizational meeting they selected property owned by DuBois, Railway Park, as the location for their baseball field. It was near Springfield's horse railway, the convenient method of transportation in the post-Civil War era. Springfield's second baseball club, the Pioneer First Company, formed by members of a volunteer fire company, would also play on the field. A visiting newspaper editor from the Pike County Democrat observed in 1867 that Springfield seemed to be afflicted with "base ball on the brain." The private park that hosted baseball also became a venue for political rallies, shooting contests and ice-skating in the winter.

As the popularity of baseball spread through Illinois and the nation, the playing fields were not available to everyone interested in the game. Sampson devotes a chapter to the efforts of Blacks and women to participate on the field. Both made efforts to be included in the growth of the game, but both were equally unsuccessful in their efforts. As the game gained popularity, the dominant male culture deemed baseball unsuited for both children and females. African-American players, while occasionally forming teams, met opposition from the National Association of Base Ball Players, who in 1867 denied the application of Black teams for membership.

Stuart Shiffman covers baseball and books for Illinois Times.