I love books. I love reading.

I am a retired librarian, so I come by this trait honestly, thanks to my profession.

I love to cook.

As a result, I have a passion for cookbooks. I have a closet full of cookbooks; they are shelved two or three deep. No, they are not cataloged, but I know what they are and where they are in my shelf arrangement.

I assigned myself a project: to learn how many African American cookbooks I owned, so I separated them out (Is that segregation?) so I could shelve them somewhere else. Not really to my surprise, as I knew I had lots of African American cookbooks, but I soon realized that I probably have more than 70: from a reprint of the first African American cookbook: What Mrs. Fisher knows about Southern cooking, 1881, to The Rise – Black Cooks and the Soul of American Food, by Marcus Samuelsson, 2020.

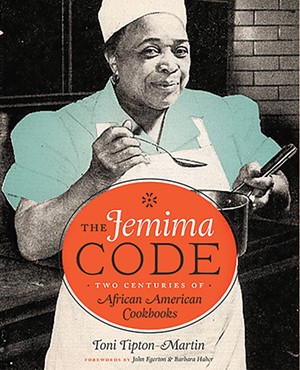

But one of my favorites, and truly one that is to be read, is The Jemima Code: Two Centuries of African American Cookbooks, by Toni Tipton-Martin, 2015. Tipton-Martin is an award-winning author who is known for her work on the topics of "cultural heritage and foodways." Recently named the editor in chief of another one of my favorites (Cook's Country magazine), she is well known in culinary circles as the "go-to person" for celebrating the professional skills and wisdom of these invisible black cooks. She is a grande dame of black culinary arts. She has amassed one of the largest collections of African American cookbooks that exist anywhere outside of a library.

The Jemima Code, which features a black cook wearing a chef's hat (not a bandana or scarf) on the cover, is a bibliography of African American cookbooks. It features more the 150 titles and is illustrated with cookbook covers and sample recipes. But what I really appreciate about the Code is that Tipton-Martin provides biographic and historical comments about each of the titles, providing not only homage to the authors, but also elevating the authors (and the cooks) to a place that they rightfully deserve: to be remembered as the ones who created sumptuous dishes from a little bit of nothing, and built businesses thanks to these cooking skills. (Think Sylvia's Restaurant in Harlem and Dooky Chase's Restaurant in NOLA.)

From the foreword, written by John Egerton, a noted journalist who writes about Southern history, food and the civil rights movement, to a second essay, written by Barbara Haber, culinary historian and former curator at the Schlesinger Library at Harvard, the Code will keep the reader interested in learning not only cookbook history but also about the how the now much-maligned Jemima figure played an important role in America's culinary history and development. She also played a role in our civil rights history, as it was the cooks in the church kitchens and "colored" restaurant kitchens (think A.G. Gaston Motel in Birmingham and the Lorraine in Memphis) who fed many of the notables in the movement. (Think M.L. King, Ralph Abernathy, John Lewis, Harry Belafonte, C.T. Vivian and others in Montgomery, Atlanta and Birmingham, etc.)

Following Tipton-Martin's introduction, the Code is divided by time periods, beginning with "Nineteenth Century Cookbooks: Breaking a stereotype" and ending with "1991-2011: Sweet to the Soul: The Hope of Jemima." The reader will enjoy this culinary ride and gain a new appreciation for the contributions of black cooks to the culinary tapestry. In the introduction, she quotes the well-known 1950s chef, Duncan Hines: "Many Southern ladies had Negro cooks to help them; and just how much we owe to their skill I have no way of knowing, except that almost all of the finest southern dishes are of their creating or at least bear their special touch and everyone who loves good cookery should thank them from the bottom of their heart" (Duncan Hines' Food Odyssey).

As I end this essay, my cookbook collection now includes Tipton-Martin's Jubilee, 2020, but I must get her other two titles.

—-

For your kitchen bookshelf

Following are some titles from each period. Do you own any of them?

Nineteenth Century Cookbooks: Breaking a Stereotype

A Domestic Cook Book; containing a careful selection of useful recipes for the kitchen, Paw Paw, Michigan, 1866

1900-1925: Surviving Mammyism

Farmer Jones Cookbook, Fort Scott Sorghum Company, Kansas, 1914

1926-1950: The Servant Problem: Dual messages

The Ebony Cookbook, 1948

1951-1960: Lifting as we climb

Historical Cookbook of the American Negro, NCNW, 1958

1961-1970: Soul Food

Mahalia Jackson Cooks Soul, 1970

1971-1980: Simple Pleasures

Spoonbread and Strawberry Wine, 1978

1981-1990: Mammy's Makeover

Big Mama's Old Black Pot, 1987

1991-2011: Sweet to the Soul

The Welcome Table, 1995

A quick trip to the local library (or Amazon) will connect you to these titles.

Kathryn Harris of Springfield is the retired Director of Library Services at the Abraham Lincoln Presidential Library (ALPL), formerly the Illinois State Historical Library, where she began her tenure in 1990. She retired from government library service in 2015. Harris was involved in the planning, development and construction of the ALPL, which opened in 2004, and considers this experience to be the highlight of her professional career. With noted Howard University historian and professor Edna Greene Medford, Ph.D., she helped design the Slave Auction exhibit in the ALPL Museum, at the request of Bob Rogers, chief designer from BRC Imagination Arts, the firm that designed the ALPL Museum.