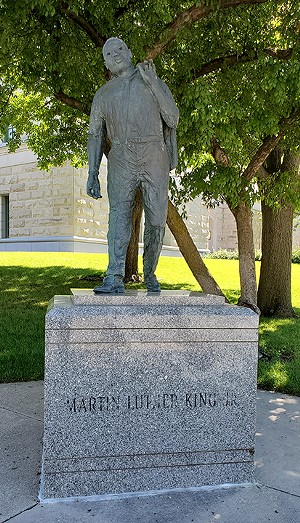

The Martin Luther King Jr. statue in Springfield is no stranger to controversy. "The placement is a complete insult to his legacy. The way it's maintained has been completely demeaning," said Dominic Watson, head of the Springfield Black Chamber of Commerce. The statue sits across the street from the Capitol, shaded under a tree.

As Confederate statues are continually and increasingly called into question, some say a harder look should be given to who is, and who is not, honored at the Illinois Capitol. And at least one statue outside the Statehouse is arguably done in a white supremacist style.

What to do with the MLK Jr. statue

A look into the history of the Martin Luther King Jr. statue shows its previous placement had also been called into question. An Illinois Times March 2017 letter to the editor from Margaret J. Collins points out, "There were three of us; Jimmie Treadwell, Lillian Kinnel and myself, who witnessed and were horrified at the 1989 placement of Geraldine McCullough's statue of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. on the walkway in back of the Illinois State Archives and the Illinois State Museum." That was before it landed its current location on the corner of Capitol and Second Streets, aka "Freedom Corner."

McCullough was a highly acclaimed African American sculptor who was born in 1917. Her family had moved from Atlanta to Chicago, where she studied at the Art Institute. Following King's assassination, she created a statue of him that went up in Chicago's west side in the 1970s. According to Austin Weekly News, the statue there fell into disrepair before being put in storage in 2011. McCullough died in 2008.

The Springfield statue was completed in 1988. According to a 2013 article in the State-Journal Register, the King statue "roamed from the Capitol rotunda to the lawn outside the Illinois State Museum before finding a home at Second Street and Capitol Avenue in 1993." It was vandalized with yellow paintballs in 2011.

Watson said he believes the statue, now situated in a way that King appears to march toward the Abraham Lincoln statue directly across the street, should be better maintained and more prominently located. But he also said he believes there should be a "bigger monument to honor his legacy."

While King was not an Illinois native, in 1965 he gave a speech in Springfield to the American Federation of Labor and Congress of Industrial Organizations (AFL-CIO) about the role of the labor movement in promoting progressive change. "Our combined strength (both the labor and civil rights movements) is potentially enormous. We have not used a fraction of it for our own good or for the needs of society as a whole. If we make the war on poverty a total war, if we seek higher standards for all workers for an enriched life, we have the ability to accomplish it, and our nation has the ability to provide it," King told the crowd in Springfield, according to the Martin Luther King Jr. Center for Nonviolent Social Change.

At the very least, that speech should be better remembered, said state Sen. Andy Manar, a Democrat from Bunker Hill. Manar said he is working with Tim Drea, president of the Illinois AFL-CIO to "raise awareness about that and to memorialize it in some way." Manar said he anticipates introducing a related resolution.

The resolution likely won't concern the statute specifically, Manar said. "My own personal opinion is we should give that statue more prominence because of Springfield and the state's role in the struggle for racial equality, and connect it to Dr. King's speech that he delivered to the state labor convention in 1965," he said.

Watson said the issue needs to be addressed so that further conversations can take place about new ways to honor the lives and contributions of Black Illinoisans. "Are we going to honor his (King's) legacy in a different way? Are we going to maintain the statue and bring it onto the Capitol grounds? That conversation leads to all other conversations."

Pierre Menard and white supremacy

Of the statues around the Capitol grounds, a prominent one features Pierre Menard,the state's first lieutenant governor. He stands over a kneeling Native American man, holding a fur. Menard was known for his fur trading. A home he lived in from 1802 until his death in 1844 in Randolph County is a State Historic Site.

"One aspect of the Pierre Menard Home that has been acknowledged, but little researched in the past, is the presence of enslaved Africans on the property between 1802 and 1848. Purchased prior to statehood, these Africans' continued servitude was insured by the 1818 Illinois state constitution. Slave labor was probably employed in the construction of the house, and slaves were later engaged as house servants and as farm laborers," said a 1999 report by Springfield's Fever River Research.

Springfield resident Vincent "June" Chappelle has a degree in Africana studies from a Historically Black University, Allen University, in South Carolina. He's now on the board of the Springfield and Central Illinois African American History Museum. "It's almost as if when they built the statue and placed it there, they were trying to make Pierre Menard into some kind of white savior," he said. "There's no reason why we should have monuments to white supremacy in our faces."

Chappelle wants the statue to go. "When it comes to the history of enslavement within the U.S. – a lot of times when we bring it up as Black people we are told to forget about it." Chappelle said it is impossible to forget about such atrocities when there are constant reminders of racism's persistence. "There is still so much to undo and make right." The Menard statue was dedicated in 1888, according to the state. The son of Menard's former business partner put up $10,000 for it.

James Loewen has long criticized Confederate monuments that he has said were created to glorify white supremacy. The sociologist and author of books such as Lies My Teacher Told Me and Lies Across America is a Decatur native. He now lives in Washington, D.C. Loewen writes about how white supremacists and neo-Confederates have found ways to spread misinformation about the Civil War by writing history books and erecting monuments.

Loewen has advocated the removal of monuments that glorify white supremacy. He has criticized a particular monument in D.C. of Albert Pike, who was a Confederate general and allegedly a high-ranking member of the Ku Klux Klan. Said Loewen in an interview with Illinois Times, "He is not a person that we should honor in any way – we should teach about him, not honor him." Earlier in June, amid widespread demonstrations against systemic racism, protestors toppled the Pike statue from its platform.

While Menard was no Confederate, Loewen said of the Statehouse statue, "There's a whole host of images like that all across the United States." Loewen said it's an example of "hieratic" art which promotes the concept of racial hierarchy. "The white person is on top, the white person in charge, a Native American is looking up to the white person in more than one way," said Loewen. "I actually think these (hieratic) monuments need to go."

Kathryn Harris is the former library services director of the Abraham Lincoln Presidential Library and former head of the Abraham Lincoln Association. She said she has also heard people propose taking away likenesses of Stephen A. Douglas, an Illinois native and Lincoln foe, from the Capitol grounds. His statue sits behind the one of Lincoln outside the main entrance of the Statehouse.

Douglas profited from a plantation in Mississippi. Black Lives Matter Springfield has said it would like to see his presence go, due to his position on slavery. "It's good that people are talking now. Because questions of race are probably the most difficult conversations that people ought to have," said Harris. But she said taking statues away "isn't going to change the story." She said she'd prefer that additional information be added to existing monuments, telling the nuances of their history and the time periods they were erected.

Meanwhile, state Sen. Manar admitted he was unaware of certain aspects of Menard's background in particular. While not advocating for immediate removal of the statue, he said, "It's appropriate, I believe, for us to come to terms with what has been, in so many instances, a brutal past in the United States."

"Should we have an open, honest and accountable debate and make a decision? Yeah, we probably should. We probably should do that," he said. Both the Illinois Secretary of State and Office of the Architect of the Capitol declined to provide comment for this story.

Contact Rachel Otwell at [email protected].