For years now, Illinoisans dismayed by their elected officials’ failure to clean up the messes they made on the voters’ behalf could console themselves with the thought, “Well, it could be worse.”

And it was, in California. Its state government confirms the truth of the old saying that California is just like the rest of America, only more so. Its politics are crazier, its finances more desperate, its special interests more insistent. Our right-thinking cousins in particular love to point to California as the liberal dystopia that looms in their nightmares after eating too much red meat. Last April, David From, Illinois director of Americans for Prosperity, damned proposals to make the Illinois income tax progressive, warning that such measures “will threaten Illinois’ prosperity by giving politicians free reign to engage in class warfare of the type seen at the federal level and in states such as California.”

Suddenly it looks – to borrow a phrase from a famous California politician from Whittier – that people like Mr. From won’t have California to kick around anymore. Only three years after it faced a budget deficit of about $27 billion, Sacramento expects to end the year at least $500 million in the black. Budgets have been cut and taxes raised, thanks to voter approval of a significant tax increase that fell mostly on annual incomes higher than $1 million. As a result, the State of California in February was given its first credit upgrade in six years, leaving Illinois as the state lowest-rated by Wall Street.

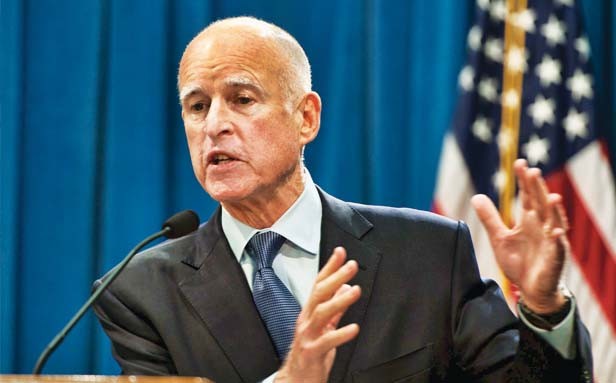

Even in the Land of the Makeover this is an eyebrow-raising turnaround. How did it happen? Part of the credit must go to Jerry Brown, the current governor. Readers younger than cell phones might be interested to learn that Brown, who was elected governor in 2010 at the age of 72, had also been elected governor in 1974 and 1978. He also served California as secretary of state and attorney general when not studying Zen meditation in Japan, volunteering for Mother Teresa in India and mayoring (for eight years) Oakland, one of the least governable cities in America. (As governor he maintains his working office in Oakland, which is a little like Illinois’ Mr. Quinn doing his work from Waukegan.)

Widely derided in the 1970s as Governor Moonbeam, Brown for years was a reason to mock California. Today – wiser, and not in the least bit sadder – Brown is a reason to envy California. Why? Because he is a politician, and a good one. Brown didn’t steer California back into deep water by being a “leader” but by assessing possibilities accurately, picking fights he could win, resorting to compromise when it was needed and exhortation only when it was likely to work.

The contrast with Mr. Quinn is plain. As a citizen-advocate and later as a largely ceremonial lieutenant governor, Quinn got experience demanding what government should do but never had to learn how to do it. Rich Miller, writing at Capitol Fax last February, observed, “Jerry Brown came into office and did exactly the opposite of what Pat Quinn did. Brown slashed government to the marrow, causing real pain. He reformed pensions. Only then did California voters agree to tax hikes.”

Just so. Before voters would consider higher taxes, they had to learn that state government was something they needed; Brown’s cuts did just that. They also need to learn that the state could be trusted with their money. That tax hike was approved by referendum (bypassing the legislature and Republican obstructionists) only because he’d baked into the plan a specific sunset provision and commitments to use most of the new money to refund schools and pay down the state debt.

I will give Brown one cheer for having pulled it off. While Brown is perhaps the most interesting person among major American politicians, it is too much to describe him as a political genius. Illinois used to routinely produce politicians with similar gifts; its voters even elected some of them governor, the most recent one being George Ryan. But these days much of the public (and much of the Republican Party) thinks that possession of political skills disqualifies a person for public office. In such dim light, a Jerry Brown will cast a shadow much larger than he is.

Still, Illinois could do much worse than to find itself a Brown, as veteran journalist James Fallows suggests in his profile of the governor in The Atlantic (“Jerry Brown’s Political Reboot”). “A country conditioned to dismiss the skills of deal making, persuasion and sheer immersion in politics,” writes Fallows, “can learn a great deal from what he has achieved.” And what is that? That, borrowing from Fallows, repairing the damage that disdain for politics can do demands an all-fronts embrace of, yes, politics.

Contact James Krohe Jr. at [email protected]