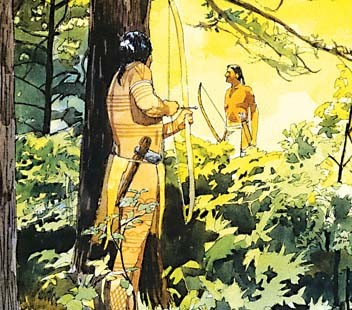

ILLUSTRATION BY ANDY BUTTRAM

“Attack on an Oneota Village,” from the collection of the Illinois State Museum.

Having some knowledge of Illinois anthropology, the boater reported the find to Michael Wiant, director of Dickson Mounds Museum. Wiant said that in his judgment the fragment is probably 700 or so years old, and that its decoration strongly suggests that it was made by people of the Oneota culture.

Oh, yes, one more question – who cares about a part of an old pot? The anthropologically literate usually explain that such a relic is not valuable for itself but for what it can might teach us about the past. These days I am more inclined to the view that such relics are valuable for what they might teach us about our present.

Consider the pot’s genesis. “The name Oneota is simply one applied by archaeologists for convenience of reference,” explained Dr. Robert L. Hall in his fine 1997 survey of North American Indian belief and ritual, An Archeology of the Soul. It refers to certain late prehistoric archaeological cultures that shared a certain level of social and political organization, made certain economic adaptations to their Midwestern environment and used certain types of tools and other objects and had certain styles of pottery manufacture.

The Oneota people were present in Illinois at the same time with people of Middle Mississippian cultures, the latter most familiar hereabouts as builders of Cahokia. Oneota culture might have been some hybrid of the new Middle Mississippian culture, it might have evolved on its own terms from predecessor cultures, it might have been brought into the area from somewhere else; maybe it was a little of all three. “Might” is a word that young archaeologists must get used to as they attempt to reconstruct history, indeed ways of life, from fragments of bone tools and clay pots. Those fragments of objects are themselves merely fragments of the lives of the people who made and used them, and studying them reveals what are at best fragments of the truth about those lives.

Most of us are content to simply make up a truth about the Native American past that we find most convenient. Some years back, an Oneota graveyard at Norton Farms in Fulton County was excavated by archaeologists before it was destroyed by construction of a new highway. The bones and artifacts found there, wrote Hall, revealed years of stressful insecurity, a result of intermittent raids by unknown antagonists on the nearby Oneota village that culminated in a final devastating attack that forced the abandonment of the village.

Nearly 300 individuals were buried in the cemetery; the skeletons of 50 show evidence of violent death over a period of years. Those still with heads had been scalped; 26 had had their heads cut off and kept as trophies. Arrows and stone axes and war clubs killed men, women and children indiscriminately. One male, age 30 to 35, must have fought like a demon, succumbing in the end to four stone ax blows to the head, two arrows in the chest, two arrows through the back and one embedded in the sternum. A child between two and three died from a blow to the head and was subsequently scalped. All the corpses were left lying where they fell for the animals to have.

The cemetery, wrote Hall, “delivers a message that almost screams to us from the graves...[about] the personal tragedies of mothers, fathers, wives, husbands and children whose long-forgotten distress still has the power after more than five centuries to shock.” It is all the more shocking to those many Euro-Americans who cling to the myth of the peaceful pre-Columbian past. Hall points out that the evidence is against the popular belief, voiced by many Indians and whites alike, that American Indians did not take scalps until they were taught to do so by the colonial English. Anthropology thus confounds the consoling simplicities that have sustained the long-fashionable romanticism about the Indian. White people didn’t invent barbarity, however much they improved it in efficiency.

New graves such as that unearthed at Norris Farms are being dug to this day all over the world – in Bosnia, in Iraq, in too many parts of black Africa. They join the uncounted graves only slightly older, in Spain, in Russia, in those parts of Asia occupied by the Japanese in the 1930s, in any place where ethnically and culturally kindred people nonetheless contrive to savage each other.

In this country, our scalpings and beheadings are only rhetorical, at least for the moment. But while contemplating the unhappy history of the Oneota, we would do well to remember that “primitive” is just another term for “human.”

Contact James Krohe Jr. at [email protected].