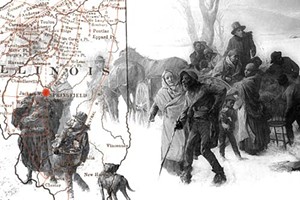

PAINTING COURTESY OF THE LIBRARY OF CONGRESS PRINTS AND PHOTOGRAPHS DIVISION / MAP COURTESY OF THE ABRAHAM LINCOLN PRESIDENTIAL LIBRARY

Charles T. Webber’s iconic painting, in the collection of the Cincinnati Art Museum, depicts African-Americans escaping from slavery. The map, from Wilbur Siebert’s The Underground Railroad from Slavery to Freedom (1898), shows Illinois routes t

Part of the intrigue of the Underground Railroad is its mystery — we’ll never know the whole story. Its activists tried to keep their work secret, so they kept no official records; many African-American participants couldn’t read or write, which prevented them from leaving records. What we know comes from oral histories, journals, and memoirs sometimes found by luck.

From available information we know that at least a half-dozen Springfieldians helped slaves escape through central Illinois. The Underground Railroad was secret because participants took enormous risks. By law, they were criminals. Those who were discovered faced official and vigilante punishment, even death. “I became so well known to the slave catchers, who used to congregate about St. Louis, that for years I would not have visited that city for any amount of money,” said Benjamin Henderson, in Historic Morgan and Classic Jacksonville, by Charles M. Eames (Jacksonville, Ill., Daily Journal Printing Office,1885). Henderson was a former slave and Jacksonville Underground Railroad conductor who brought slaves to Springfield. “It is now rather a matter of pride to be reckoned among the abolitionists of those days, but it was not so then,” he said. “A good many now lay claim to the title whom I never knew as such until after the war.”

Henderson described another Jacksonville Underground Railroad conductor, Dr. M.M.L. Reed, whose activism “cost him daily in a financial way, beside endangering his life and greatly destroying the peace of his family.” Henderson said Reed was so hated by slavery supporters “that for years he seldom felt safe in walking on the sidewalk at night, taking the street to avoid a possible unseen enemy. One night during his absence his family had reason to believe an unsuccessful attempt was made to set his house on fire.”

How, and even whether, the Underground Railroad operated in a given area was determined by the political makeup of that area. Politically, Illinois was a land of opposites. Southern Illinois was largely pro-slavery, thanks to the many Southerners who moved there. “The southeastern part of Illinois contained few or no [Underground Railroad] lines,” wrote renowned Underground Railroad researcher Wilbur Siebert in his 1898 book The Underground Railroad from Slavery to Freedom (New York, Macmillan), based on Underground Railroad oral histories from around the country.

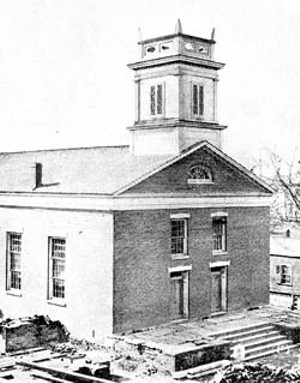

PHOTO COURTESY OF WIKIPEDIA

John Cook, a Union colonel from Springfield, was credited with hiding escaped slaves, according to a memoir in the Sangamon Valley Collection of Lincoln Library.

Springfield, in the middle of the state, was home to a mix of opinions on slavery. Many fugitives escaped to Illinois from Missouri, where slavery was legal, according to Glennette Tilley Turner’s The Underground Railroad in Illinois (Glen Ellyn, Ill., Newman Educational Publishing, 2001). They entered Illinois through Alton, Quincy, or Chester. Fewer came through Cairo, which was more dangerous because of local slavery supporters. Slaves usually came to Springfield directly from Jacksonville or Farmingdale (then called Farmington). Both towns were known for their abolitionist views and had Underground Railroad participants. (The Illinois Anti-Slavery Society even held its first-anniversary meeting in Farmington.) “In 1841 these fugitives from slavery first began to come through Jacksonville and from that time this has always been a station on the Underground Railroad,” said Julia Carter, the daughter of Jacksonville Underground Railroad conductor Elihu Wolcott (in the Feb. 4, 1906, Jacksonville Daily Journal). “Ben Henderson, among the colored people here, was the one to whom they all went.”

Henderson related some of his experiences in Historic Morgan and Classic Jacksonville. He said he worked on the Railroad from 1841 until 1857 or 1858. “A fine looking couple once asked me for shelter,” he said, “in great haste. The hunters were hard after them and $1,000 reward was offered for their capture and return. I was then closely watched and hardly knew what to do. Finally I made an excuse to take some hemp cradles to Springfield, so I laid some hay in the bottom of the wagon, put my passengers on it, more hay over them, and my cradles on top of it and drove leisurely through town about the middle of the afternoon and got through all right.”

During the winter of 1853-1854, another African-American from Jacksonville, David Spencer, transported eight runaways by way of the Great Western Railroad (his story is also from Historic Morgan and Classic Jacksonville). They boarded the train at Jacksonville just before daylight, Spencer said. “When asked several times who my companions were I replied that they were friends from Chicago who had been here to spend the holidays. Soon after we started one of the men whispered in my ear that his old master was in the car a few seats ahead of us, no doubt on the hunt for his property,” Spencer recalled. “I told him not to be afraid, for I had a revolver with me and would use it if I had to do so. To our great relief, the slaveholder left the train at Springfield, little thinking who had been riding with him.”

Once slaves reached Springfield, who took care of them? Local attorney and historian Dick

Hart researched that question extensively and published the results a couple of years ago in the booklet “Lincoln’s Springfield: The Underground Railroad,” available from the Sangamon County Historical Society (308 E. Adams St.). Hart found that two white and four black men from Springfield were Underground Railroad conductors. The whites included Luther Ransom, who’d been active with the Railroad in Farmington before moving to Chatham and then Springfield. He ran a boardinghouse near the Globe Tavern (on West Adams Street), where Abraham and Mary Lincoln lived when they first married. Erastus Wright was the other. He lived near the intersection of Jefferson and Walnut streets and was a teacher, Sangamon County school commissioner, and member of the Second Presbyterian Church, known as “the abolitionist church,” according to Hart. It’s now called Westminster Presbyterian Church. Other members of that church helped the Underground Railroad, too, according to church history. Of the four black Underground Railroad conductors Hart found, three had ties to Abraham Lincoln. Jamieson Jenkins was a neighbor, living just south of the Lincolns on Eighth Street. A series of newspaper articles in mid-January 1850 links Jenkins, a drayman or wagon operator, to a group of runaway slaves who escaped through Springfield and suggests that he may have helped them [see Tara McAndrew, “A conductor?” Illinois Times, April 3]. Jenkins was a member of the Second Presbyterian Church until 1851.

The Rev. Henry Brown worked for the Lincolns as a laborer and led Lincoln’s horse in his Springfield funeral procession. Hart found that he’d helped escaped slaves in Quincy and Springfield. Aaron Dyer didn’t have ties to Lincoln, but Hart notes his other interesting connection. Dyer’s grandson William Dyer became friends with renowned writer William Maxwell, who wrote a short story about “Billie.” Both Billie and his sister Harriet talked about their grandfather’s Underground Railroad work in Springfield. They said that Aaron, a blacksmith and drayman, “drove his horse and wagon at night, taking runaway slaves to the next underground station.”

COURTESY OF LINCOLN LIBRARY’S SANGAMON VALLEY COLLECTION

An illustration of Second Presbyterian Church, which had the reputation of being Springfield’s abolitionist church, from the 1840s.

Donnegan described a harrowing experience helping a teenage slave. She wouldn’t follow directions and narrowly missed being spotted by her master, who’d followed her here. “I knew the house would be watched all night,” Donnegan said. “I heard in the afternoon that about thirty men had been engaged about town for that night. A full description of her had been given in the Springfield Register with an offer of, I think, $500 for her capture.”

He bought the girl white gloves and “a white false face, told her what to call me and what to talk about” and how to alter her voice, “so if her master heard her he would not know her.”

During the night, Donnegan whisked the disguised slave away, but her master and armed slavecatchers tracked the duo and blocked their way. Donnegan outsmarted them by sneaking into a church, then his brother’s house. There they dressed the girl as a boy and sent her with a work gang the next day to a nearby abolitionist’s.

Fifty years later Donnegan, then 84, was lynched during Springfield’s race riots. I recently found a memoir at the Sangamon Valley Collection that provides new insights about other Springfieldians who helped slaves. The memoir describes Thomas Madison Davis, an escaped slave who fled to Springfield; it was written by his son, John. It tells how “Tom” and other slaves were hidden by sympathetic Union Col. John Cook of Springfield while he and his troops were stationed in Paducah, Ky. “[Cook] hid the fugitive slaves as long as he could, but finally called them together and told them that Kentucky was not in rebellion against the United States and they had the right to come every day and seek for their slaves. (During the last search, Tom was hidden in a flour barrel),” the memoir says. Cook told the men he couldn’t “protect them any longer” and put them “on the Illinois side of the river.”

The group traveled north and arrived in Springfield on Christmas. Tom lived at 219 N. 15th St. with James Henderson Lee, “a good religious man of color” who “had built a house so that any runaway slave who wished to live respectably, might have a place to stay, free of charge until he got on his feet,” the memoir said. “He called it ‘The Young Men’s Aid Society.’ ”

Famed abolitionist Seth Concklin may have helped slaves through Springfield, too. He knew about the state’s Underground Railroad lines, according to an 1851 letter he wrote (published in The Underground Rail Road), describing a route “through Illinois, commencing above and below Alton.”

“In Springfield, Illinois, [Concklin] aided fugitives escaping on the Underground Railroad, but seldom acted in concert with others,” wrote Betty DeRamus in Forbidden Fruit: Love Stories from the Underground Railroad (New York, Atria, 2005).

Members of Springfield’s Zion Missionary Baptist Church came here by way of the Underground Railroad, according to The Underground Railroad in Illinois. And a Springfield black man named Free escorted runaways between here and Chicago, according to Delores Saunders’ Illinois Liberty Lines. “He nearly met his ‘Waterloo’ one time when pursuers gave chase and overtook him near Washington, Illinois,” she writes. “He was shot and badly wounded.”

The Springfield-to-Chicago line of the Underground Railroad was popular, and disguised slaves often traveled it by stagecoach, Saunders adds. “It was a familiar sight to see a Negro man or woman dressed in a long flowing gown, wearing a fashionable hat, heavy black veil and gloves. Carrying ‘her’ carpet bag and purse, this passenger sat in sedate form. A sign was placed around ‘her’ neck which read, ‘Deaf and Dumb.’ ”

“There is so much that needs to be understood about the Springfield Underground Railroad, but there aren’t many primary materials about it,” says Curtis Mann, city historian. Unless more materials are discovered, the whole truth will remain a mystery.

Tara McClellan McAndrew writes a history column for Illinois Times.