What do you call someone who hangs around with musicians?

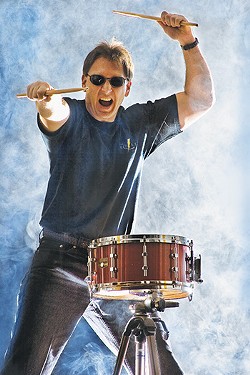

A drummer.I don’t know why I have always enjoyed drummer jokes. My father is a professional drummer, and a fine one, so one should not read anything Oedipal into this odd taste. I have yet to recognize any aspect of his playing or his personality in any drummer joke.

I have, however, recognized bits of myself. We had to take music lessons when I was a boy at Matheny School, and I took drumming because it promised to be the easiest. My performance thoroughly refuted the idea that talent is genetically transmitted. I was a right-handed kid trying to master a craft that requires a left hand as well, and an undiagnosed myopia made it hard for me to read notes. Sight-reading a percussion part for me was like looking for a house key in a cluttered room with the lights out.

I did make the All-City Grade School Band, but I suspect it was because the fix was in; they wanted to leaven all the west-side kids in the band with a few of us east-siders. I could play the snare drum only after painfully working out the part and memorizing it, so I was asked (or did I volunteer?) to play the bass drum. This I did by imitating the technique used by a chimpanzee I saw on “The Ed Sullivan Show.” I did however look great in my uniform.

Lots of people don’t regard drums as musical instruments. (The wider family of percussion instruments, which include chimes, marimbas and the like are a different matter.) I believe that the opinion owes to the fact that few mainstream American music listeners have ever heard drums played really well. Not without reason did Village Voice rock critic Robert Christgau used to helpfully warn readers if a new album had drum solos on it.

Drums certainly weren’t musical the way I played them.

How is a drum solo like a sneeze?

You know it’s coming, but there’s nothing you can do about it.

One who could make music with a drum set was Springfield’s most famous musical son. Barrett Deems was born in Springfield in 1914, grew up here and lived here on and off, although his main base of operations was Chicago. Deems reportedly was a hyperactive child who matured into an eccentric and interesting man, although one who was by all accounts loud, pushy and hyper, the kind of guy whose company was more pleasant in memory than it was in the moment.

Deems mastered the hardest part of being a drummer, which is making a living at it. He was good enough to be hired by the likes of Joe Venuti, both the Dorsey bands, Beardstown’s Red Norvo, pianist Art Hodes and Jack Teagarden, and he kept getting hired over a 70-year career.

What is the difference between a drummer and a savings bond?

One will mature and make money.

Deems’ most famous bandmate was Louis Armstrong, with whom he cut some seminal recordings. He was billed as the “world’s fastest drummer” made him sound flashy and vulgar, but he kept good time. Not all drummers do.

“Hey buddy, how late does the band play?”

“Oh, about half a beat behind the drummer.”

Did you hear about the drummer who tried to commit suicide?

He threw himself behind a train.

Deems specialized in New Orleans jazz dating from the early 1910s and big band swing. He also led what has been called a top-notch jazz band for years at the Brass Rail on Chicago’s Randolph Street. Big bands are clumsy machines and they need someone to push them to make them go, and that someone is the drummer. It is widely believed that white musicians tend to be a little early on the beat by a matter of milliseconds – what’s been called the honky offset. The result is a style usually labeled “propulsive.” It might explain why our greatest African American jazz band leaders put white drummers in their otherwise black bands. Deems, as mentioned, worked for years with Louis Armstrong, and Louie Bellson (also an Illinoisan, by the way, from the Quad-Cities) was hired by Count Basie and Duke Ellington.

The only big band I was in was the symphonic band I found myself assigned to at the band camp I attended when I was 13. All I knew about tympani was that they existed, and there I was on the first day, standing in front of a pair of kettle drums, facing a score of Wagner’s “Die Meistersinger,” in which the notes went up and down as well as stopped and go-ed. As the conductor proceeded from the podium to lay out the schedule for the coming horrors, I sat down – only to find that one of the older boys had pulled my chair away.

I learned a lot about music that day – mainly that drummer jokes aren’t funny if you’re the punch line.

Contact James Krohe Jr. at [email protected].